Few artists’ work is more instantly recognisable than that of British artist Julian Opie. Celebrated for his minimal yet distinctive visual language, Opie brings his observations of the contemporary world to life. Through a reductionist approach, he strips away layers of his subjects to essential black lines rather than lifelike accuracy, unveiling their essence through the tiniest of details, occasionally punctuated by flat colours. Playing with what he sees in nature and culture, Opie depicts these experiences in a visual dialect that immediately captures attention.

Born in London in 1958 and raised in Oxford, Opie attended The Dragon School before moving on to Magdalen College School from 1972 to 1977. He then studied at Goldsmiths’ College (now Goldsmiths, University of London) under the tutelage of conceptual artist and painter Michael Craig-Martin, graduating from the institution in 1982.

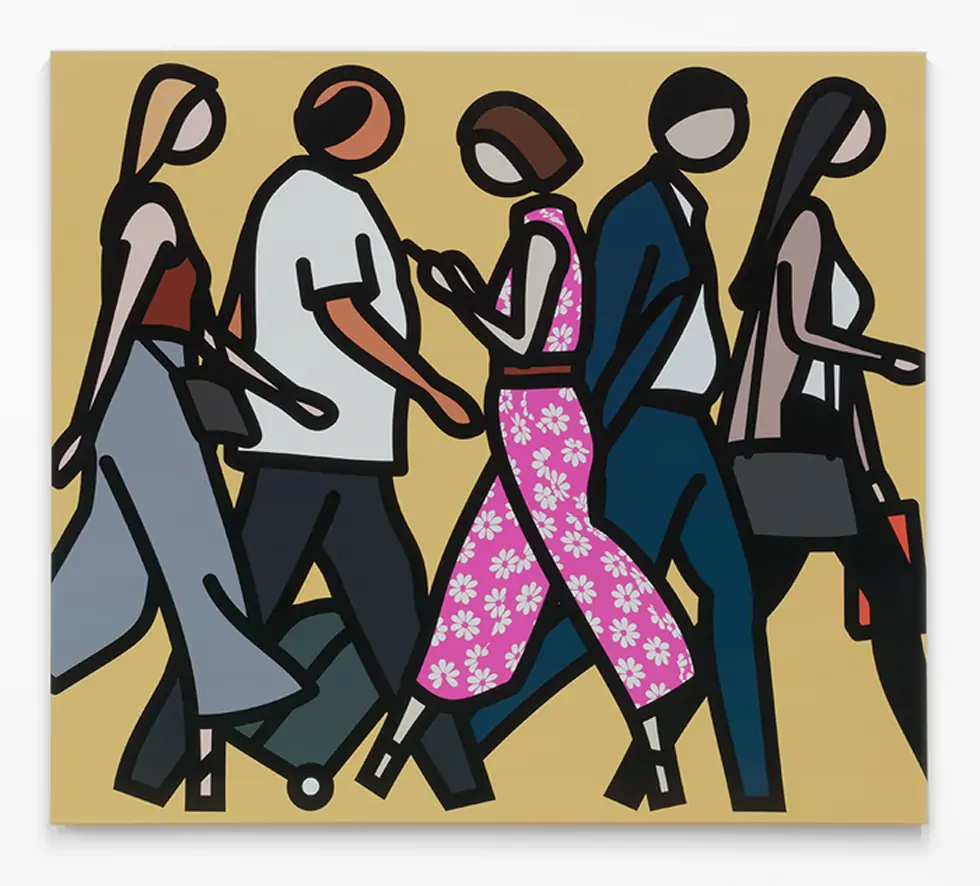

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

I play with what I see in nature and culture, in my own and other artist’s work. I gather and mix, trying out possibilities in my head. I can build works and whole exhibitions in my head. It’s a gift.

Julian Opie

Opie made his art world debut in 1983 with his first solo exhibition at London’s Lisson Gallery. This milestone marked the beginning of his successful career. Closely associated with the New British Sculpture movement, Opie was recognised as the youngest of the ‘New British Sculptors.’ During its peak in the early 1980s, this movement embraced a more traditional approach to materials, techniques, and imagery in response to minimal and conceptual art.

Opie’s practice is characterised by his use of new technology, fascination with the human body, and engagement with art history. This combination of interests empowers his challenge to traditional ideas of representation, as he delivers commentary on contemporary life. As technology evolved during the 1980s, he began integrating movement into his art, progressing from early computer monitors to wall-based flat screens and onto LED public signage. Utilising digital processes to manipulate photographs and videos into stylised representations has become a signature of his work.

Best known for his striking portrayal of walking figures, Opie reveals the human condition of movement in a simplified form. His figures, often in motion—walking, dancing, or blinking—are captured in looped animations that highlight the repetitive nature of modern life. Walking is elevated from a routine of physical activity to a subject of analysis, a motif symbolically abstract yet universally recognised. Opie renders these figures in various mediums, from tubular steel sculptures to beads and wood, digital screens, and paintings.

When I view Opie’s walking figures, especially his digital editions, they encourage me to pause and reflect. As my eyes follow the looping animation back and forth, my thinking begins to mirror what is before me, prompting me to ask myself, “Where am I going?”

Opie has exhibited worldwide, with solo shows at the National Portrait Gallery in London and MoMA in New York. Notable projects include his album cover design for the Britpop band Blur in 2000, which reimagined the band through an uncomplicated lens. This series of portraits became iconic in their own right and is now located in London’s National Portrait Gallery. Another influential piece is his “Walking in Melbourne” series of sculptures, life-sized figures encapsulating motion in stark, linear forms. Some critics argue that Opie’s work lacks emotional depth and is too focused on aesthetics and form.

However, what I find most compelling about Opie’s work is its accessibility. Its beauty lies in its ability to communicate universally, extending beyond the confines of gallery walls to public spaces. Installed outdoors, his art interacts with its environment and the people, bringing art into everyday life.

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

This July, Opie’s sleek-lined pedestrians were Walking in Milan as the artist opened his new exhibition at Portrait Milano, creating eight new public sculptures caught in motion. Piazza del Quadrilatero is located in the heart of Milan’s Quadrilatero fashion district. With a vast courtyard of approximately 32,000 square feet, it is the largest public square in the district. Opie’s sculptures will inhabit its courtyard, engaging with passersby as they walk between the neighbourhoods two main streets, view its architecture, or staying at the decadent Portrait Milano. Once a seminary hidden away behind closed gates, Piazza del Quadrilatero is the ideal stage for his figures’ ritual of walking.

Opie’s ability to distill subjects from ordinary life into vivid symbols reflects society’s connection with digital media and streamlined communication, making his work more relevant than ever in this ever-evolving digital terrain. We managed to catch up with the British artist ahead of his exhibition at Milan’s Portrait Milano to learn about his practice, inspiration, and more.

Auto paint on aluminium

105 x 79 x 3 cm

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

Hi Julian, Can you share some early moments from your journey into the arts and what motivated you to pursue a career as an artist?

Julian Opie: As a child my family had paintings on the wall, mostly reproductions of English post-war art, and I remember staring at these and imagining myself in the spaces depicted. I grew up in Oxford, and at secondary school, I would wander the amazing and famous local art museums, both historical and contemporary, with headphones on. There was also an anthropological museum in Oxford that fascinated me, full of objects and statues from around the world. I did not really think about creating art; I just drew things all the time. It was a habit and a way of thinking and having fun.

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

Your minimalist-style portraits and animated walking figures, which seamlessly blend new technologies with art historical themes and utilize the human form as a muse, have garnered international acclaim and offer commentary on contemporary urban life. Can we delve into your practice, creative process, sources of inspiration, and the themes in your work?

Julian Opie: I play with what I see in nature and culture, in my own and other artist’s work. I gather and mix, trying out possibilities in my head. I can build works and whole exhibitions in my head. It’s a gift. I get very excited and start lots of projects gathering technologies and resources. Then I usually get scared and often panic, but out of the scramble to save the project – the compromises and last-minute inventions – comes a new solution. Seldom quite what I had wanted, but a small step from where I can often see more possibilities.

Additionally, your use of minimal detail and black line drawing is quite distinctive. Can you describe your process for deciding how much detail to include or exclude in a piece?

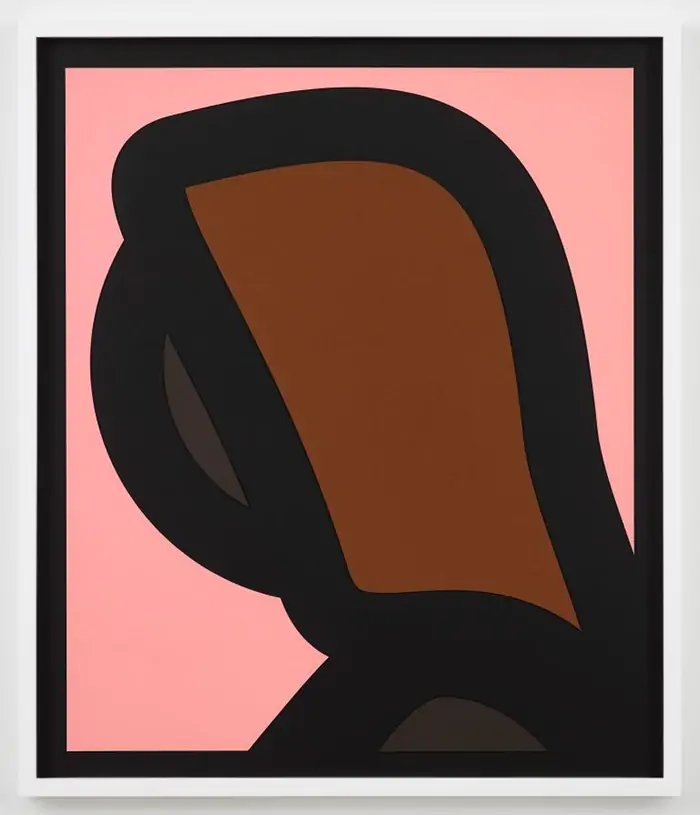

Julian Opie: There is an element of mechanical process in all drawing, of flattening out what you see and developing a language to translate the endless complexity of reflected light into an adaptable set of signs. By placing a photograph of a friend over a shop-bought lavatory sign, I was able to adjust the universal symbol for man or woman into a symbol for a particular individual.

I reused this process and “zoomed in” on a face. I aimed to make a kind of rubber stamp for every face, a universal logo for each person I saw. I may have drawn hundreds of faces, but I still look at people on the subway and want to draw each face using the systems I have developed.

Laser-cut archival Museum Board in frame

83.4 x 71.1 x 3.9 cm

Animated walking figures are a hallmark of your style. What inspired you to explore this form, and how do you approach capturing movement with such simplicity?

Julian Opie: I have made a lot of artworks of people walking, it’s true. I keep thinking I should stop, and then something else occurs to me to do. Back in the 1990s, I found a way to draw people, but it was people standing like statues. Like posed photos, I drew everyone I knew like that. One day , I was sitting in my car waiting for one of my children to come out of school in a bored semi-trance when I saw the people passing by as a kind of picture, like a classical frieze of dynamic bodies that flowed endlessly like a river. I imagined drawing the individuals and combining them into crowds.

There is an endless supply of people walking past me to draw, and I have used pedestrians from many countries, including Japan, Korea, Australia, America, India and Belgium. The way I draw the people renders them fairly roughly, using a limited vocabulary of line and form like hieroglyphs, but I think they remain individual, each person particular and connected to reality like a shadow relates to an object.

Auto paint on aluminium with concrete base

280.6 x 124.9 x 5 cm (175 x 70 x 70 cm plinth)

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

In describing your approach, you have mentioned that striving for realism serves as a fundamental criterion, along with considerations such as whether you would like to display the piece in your own room and envisioning if it would be worthy of presenting to God for judgment. Could you elaborate on how these benchmarks influence your creative process and decision-making?

Julian Opie: A shadow is basically the same as a photograph; if you see a shadow at night of a tiger or advancing robber, your body jumps as it reacts to the image that is itself an extension of reality. A drawing can have the same quality. I collect child sized Indonesian wooden statues, and in my peripheral vision, they make me react as if a real person was present. We are hardwired to respond to the visually perceived world.

IF I TYPE IN BOLD, it feels different from the softer words written in italics. It’s not really possible to predict exactly how these things work. I have tools such as materials and scale, colour, movement and reference that allow me to play and experiment with subject matter to see what is possible, what feels right and exciting.

Warhol once wrote of making art: “If you have to make a decision then something is wrong.” I think he meant that each step should come as a logical and inevitable result of the previous premise. I hate arbitrary decisions and am always looking for that hidden logic. I work most days and have a system of testing and trial and error. These days I use VR goggles to be able to look at works in real space and time and to create the layouts for exhibitions.

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

Designing an album cover for the Britpop group Blur was a significant commission, initially as a CD cover and later as a set of portraits in the National Portrait Gallery. What was your approach to this project, and how did you ensure it captured the essence of the band?

Julian Opie: Doing projects like this is an exciting step out of the usual museum and gallery shows that I am lucky to do. I make public projects quite often and I also value the way these allow me to expand my vocabulary and engage with other kinds of spaces that are outside what is called the Art World.

Looking ahead, given your extensive career, how do you see your practice evolving? What new directions or mediums are you excited to explore in the future, and how do they differ from or build upon your past work?

Julian Opie: As I said, large scale interests me a lot at the moment, and also using raw materials to draw with, like steel or concrete, rather than covering the structural material with a skin of paint. I try to break free from my own look and way of reading the works, but in the end, I keep circling back to similar conclusions. Perhaps now I have more experience and certainly more resources.

It’s a fear that it gets harder to break away from territory you have established, but it’s also a good thing I think to make full use of what you own. I work in quite an instinctual way following my interests. Currently I am working on a series of sprinting athletes borrowed from the GB Olympic team and a group of some 20 children ranging from 4 to 8 years old.

The sprinters move on a brilliant flowing motion that is barely possible to capture, and the children, by contrast, walk in a very idiosyncratic way full of character. Once I start such a project with models and cameras and repeated sessions, I let things develop as they will. As I work certain things seem possible, and I start to experiment with paintings, sculptures and films. I even have been experimenting with VR environments and automatic drawing programmes.

Image courtesy of the artist © Julian Opie

Looking back on your career, which spans four decades, you have achieved a lot with your work. How do you wish to be remembered in the art world? How do you envision your work and impact influencing future generations of artists?

Julian Opie: I tend not to look back and have no pretensions as to influencing others. I hope I have managed to provide some entertainment and maybe some sense of communicated thought-process and outlook.

Lastly, could you share your philosophy of art? How do you describe and understand the core importance of art in your life and career?

Julian Opie: This is a very grand question and not one I can come at directly. I don’t have a set rule book or map. I could use a favoured quote of Shakespeare. A character claims, “I am not an honest man but am sometimes so by chance.” I could change the word honest for clever. I work hard most days to set up situations where that element of chance might outpace my limited thinking and catch some fleeting truth about what it’s like to be alive.

https://www.lungarnocollection.com/piazza-del-quadrilatero

©2024 Julian Opie