Saatchi Gallery presents 2024 RHS Chelsea Flower Show Zak Ové garden. multi-disciplinary artist Zak Ové has collaborated with Saatchi Gallery and award-winning Garden Designer Dave Green on its annual garden at RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2024.

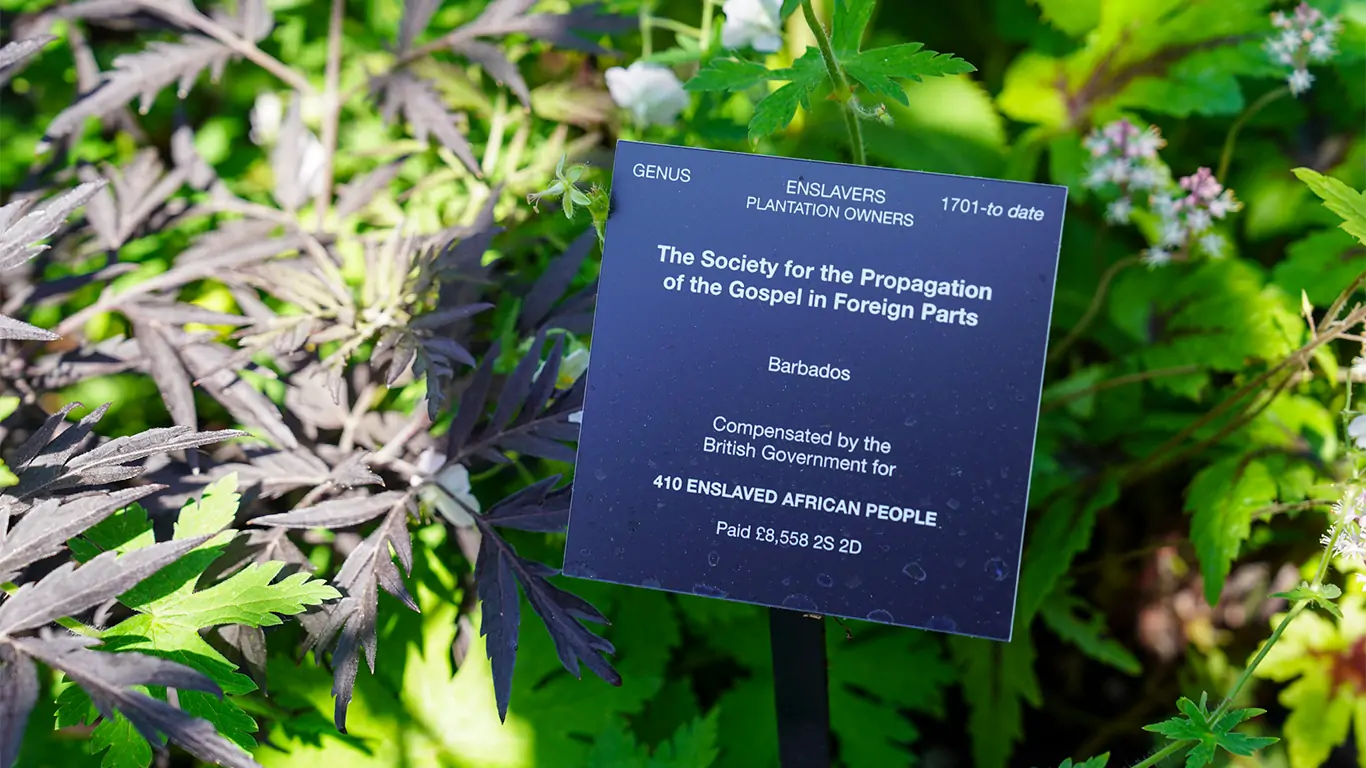

Titled Abeba Esse, the garden depicts a Black Diasporic journey from Africa to the UK via the Caribbean through plants, flowers and sculpture. Visitors follow a path through a Caribbean landscape to an English country garden, encountering Ové’s Invisible Man sculptures along the way, and botanical labels planted in the soil are inscribed with information about key players in the shameful slave trade.

Images Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London © Harry Sweeney

I was interested in the many layers of the Slave trade, the journey of the African Diapora but the trail of the money, beginning in Africa as a ‘Paradise Found’

Zak Ové

Abeba Esse encourages important conversations about the themes central to Ové’s work – African Diaspora, contemporary multiculturalism, globalisation, and the blend of politics, tradition, race, and history that informs our identities.

Lee Sharrock: The garden’s title ‘Abeba Esse’ is derived from ‘Abeba’, the Ethiopian for flower, and ‘Esse’, meaning essence or the essential nature of something, and both words are Palindromes, meaning they can be read the same backwards or forwards. How did you come up with the title?

Zak Ové: I wanted something playful and African sounding. Due to the serious topic matter, I wanted a title that was attractive and ‘light hearted’ – like attracting bees to the honey…. so to speak. Palindrome’s have that playfulness, of reading back and forth, I like that movement, it echoes the movement found in elements of my practice with a return to the past from the future and back again, of reciprocal time travel. The sculptures that I’ve placed within the garden were originally created for an installation at Somerset House entitled: ‘The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness’ (1.54 Art Fair).

‘The Masque of Blackness’ was a play written for Queen Anne in 1605. Queen by Ben Johnson, with Inigo Jones creating costumes, sets and stage. What I was fascinated by was the script that they were personifying in the actual performance. In the play nine English princesses play Deities from the Niger Delta, who have to come to Britain to bathe in a sea of whiteness in order to proclaim their true beauty. They were played by nine English Princesses, Queen Anne included, and it was the first ever use of ‘Blacking Up’. This was 3 years after ‘Macbeth’ was written, post which King James ramped up the trade in enslalved Africans. I made this as a kind of rebuke in that situation. I like the fact that my figures are sculpted in the past and forged in the future.

Lee Sharrock: So there’s an Afrofuturism relationship to the sculptures?

Zak Ové: Yes you could loosely call it that. But the thing I liked in particular is the idea that they come from the future as Time Travellers to investigate their own history. To unearth the invisible history that was never really spoken about, and a history beyond that, which was given to them by so called, Colonial Masters, in place of any real investigation of their own. That was my point of reference. A lot of my work is to do with the unveiling and re-telling of invisible histories.

I was interested in the many layers of the Slave trade, the journey of the African Diapora but the trail of the money, beginning in Africa as a ‘Paradise Found’, moving through to the Caribbean, shown here with tilled earth, as a marker of the beginning of monoculture and finishing in an English country garden, common to stately homes. What I’m looking at is how the money from slavery financed many of these situations.

Lee Sharrock: Financed these country homes

Zak Ové: Yes, many of them. It’s all there in the records. The vast sums of money awarded from the compensation scheme in 1833, and the flow of money that came from imported goods from the Caribbean.

Lee Sharrock: Are these the same sculptures you exhibited at Somerset House?

Zak Ové: Yes, the sculptures were at 1.54 Art Fair, then they went on to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the Rodin Garden at Los Angeles County Museum and San Francisco City Hall. So they’ve toured quite a few locations already.

Lee Sharrock: Is there any relationship to when Picasso and the Cubists plundered African art and sculpture and called it ‘Primitivism’, or the way that Western artist referenced African artists?

Zak Ové: No, I wouldn’t say so. I don’t look at these as Primitive in any shape or form. A lot of my practice is really looking at old world cultures and Old World mythologies, and using New World materials, that give them a new lease of life and opening them up to a contemporary conversation.

Lee Sharrock: So they’re more like visitors from another time period?

Zak Ové: Yes in this instance I’m playing that game. I like the idea that time is reciprocal, and I’m very interested in the idea that in African culture, we move forward to the future with our ancestors. So it was really embellishing that view point with a deeper understanding of the culture that they come from.

I would never contextualise them as primitive. Not even in the instance in which they were made. I think Primitive is a title that was given by Colonial Conquistadors, which simplifies what this work was about, without any real value of its history its connotation to the history of Africans, how history was recorded, why the sculptures were used in the way they were used ceremoniously. So I think it’s quite the opposite for me in that sense.

Lee Sharrock: You worked with garden designer Dave Green on the Saatchi Gallery garden to depict a African diasporic journey from Africa to the UK via the Caribbean, using sculpture, plants and flowers. How was the collaboration and did you do a lot of research together?

Zak Ové: Working with Dave has been really easy, due to his extensive experience and knowledge. We discussed at length the design and types of plants available in our short time frame, and the placement.. We only had three months to put the project together, so we had to make use of the available resources during this time – I would have liked other things that weren’t available like Cotton trees or flowering tobacco plants, but that takes long term planning. But I’m super happy with David’s interpretation, I think it’s fantastic, it’s what I envisioned.

Lee Sharrock: Garden design and horticulture is an art form in a sense. As a multi-disciplinary artist, how do you find the creative process of garden design, did you enjoy creating a garden, and how did it work marrying your art with garden design?

Zak Ové: I’ve really enjoyed it. I enjoy art placed in nature. Normally they’d be seen in a clinical white room. So I think it gives them a sense of context.

Lee Sharrock: Do you think the garden makes your art more accessible for people, and makes it more immersive in a way?

Zak Ové: I don’t know if it makes it more accessible. I don’t think they’re not accessible. but I think it gives a context to their background, their history, and the story that I’m using them to represent in this instance.

Lee Sharrock: The botanical labels in the ground, which look like they might be the plant names, are actually based on names of people that benefitted from the slave trade. How did you decide on what names to feature here?

Zak Ové: The research was all done through the UCL website, which is completely accurate and factual. I was interested in highlighting some of the principal individuals and institutions, that developed the Slave trade, and people like Sir Moses Montefiore and his brother in law Nathan Meyer Rothschild, known as ‘the Rothschild syndicate’ they were awarded the contract to raise the loan that financed a £20 million compensation scheme for owners of 800,000 enslaved Africans. The Bank of England paid out nearly 45% of what it had in compensation in that point in time. The compensation payments of those loans were only completed in 2013. If you think of a country like Haiti, it’s still paying reparations to France for loss of income from the trade in enslaved Africans. What’s fascinating to me is that, this is a history that I was never taught in school, and it’s my history and it’s very important to understand how the money moved in the UK, and what it then supported post Abollition. The British Empire grew on the money that came from Slavery.

Lee Sharrock: Why do you think this conversation is only now coming to the forefront?

Zak Ové: Because I think it’s a conversation that people don’t want to have, quite literally. We’re not taught about the movement of money or the compensation schemes that were paid out to secure Abolition. It was massive amount of money, the largest government bailout until the bank bailout in 2009..We can go through this garden and look at what different people received in compensation.

It was monstrous. I’ve included two barrels full of murky water in the garden to reference the water that was carried on the enslavement ships.20% of enslaved Africans held captive – over 1.5 million died on the ships many literally dying of thirst. It’s quite incredible when you think of how many people were transported, and then obviously the children they had who were born into slavery, and how that extended and extended.

Lee Sharrock: So the generational trauma needs to be acknowledged by the institutions and people who benefitted from the slave trade, and someone should be compensated. And basically all the institutions were involved, including the Church of England?

Zak Ové: £433 million in today’s terms were invested by the Church of England in the South Sea Company, who were big traders of enslaved Africans. Queen Anne dramatically expanded the nation’s slave trading activities by trading slaves from South America to other European countries who were extending their own empires and colonies.

Lee Sharrock: It’s such a strange concept to think it was acceptable to buy a person, that a human being could be traded. And that so much money was made out of it.

Zak Ové: Yes, and this went on for more than 300 years. It changed the face of the British landscape forever, many our Stately homes, businesses and our trading abroad was all based on the value of this currency (people). It was also the beginning of Monoculture in the Caribbean, because Islands like Barbados were stripped of any produce other than tobacco, cocoa, sugar etc. It was the beginning of our environmental disasters also, because that same mentality was taken and put into how those landscapes were planted and what was removed. In the garden I’ve planted fists coming out of the ground to represent ‘seeds of resistance’. Because rebellion was a daily occurrence, and the treatment of the enslaved Africans was horrific.

Thomas Daniel, who has a label in this garden, was one of the largest enslavers in Barbados. There is plaque placed by TTEACH in Bristol Cathedral. I’ve been working with an organisation called T Teach, which is run by a lady called Gloria Daniels. Her surname has a direct lineage as a slave to Thomas Stanley, as do her ancestors. It’s incredible to think that some people still carry the names of their slave owners and have no knowledge of their own histories. It’s deplorable.

Lee Sharrock: It’s so important to have exhibitions and installations like this and the education that you’re giving people.

Zak Ové: Thank you.

Zak Ové’s Saatchi Gallery 2024 RHS Chelsea Flower Show Garden is at the Royal Hospital Chelsea until 25th May, 2024.

©2024 Zak Ové