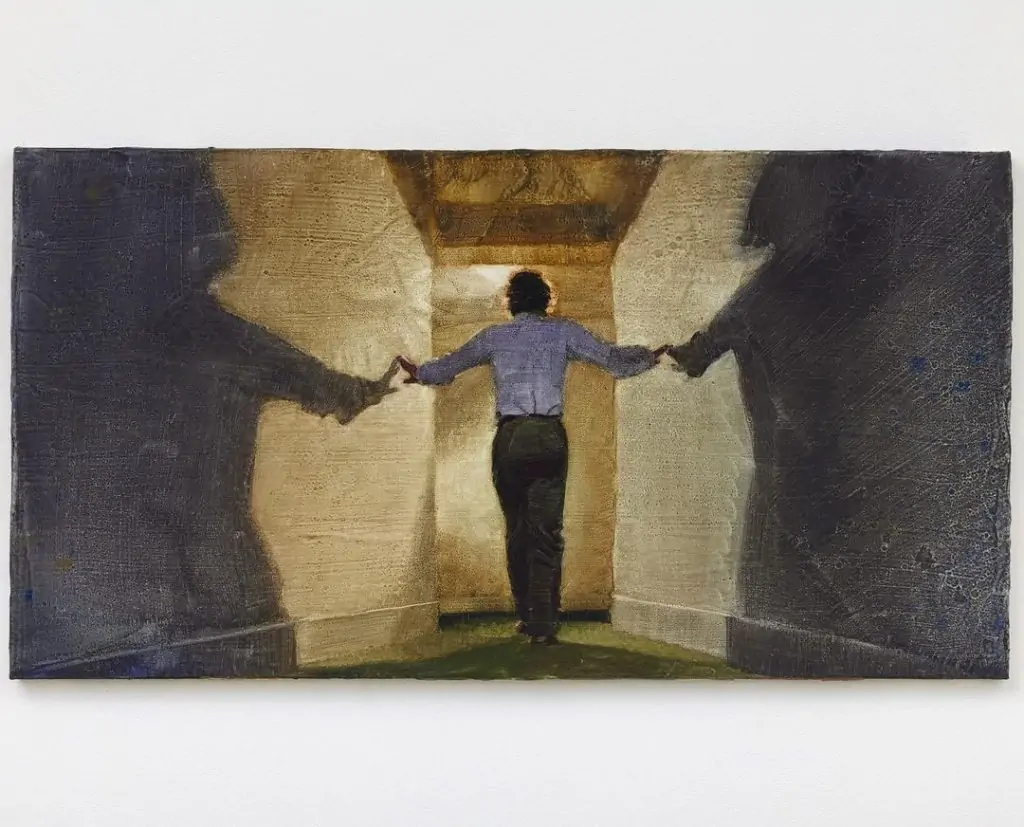

Emerging realism painter Joseph Yaeger casts a cinematic spell with his paintings, brimming with lifelike detail, enhanced by his magnificent use of lighting and framing. His canvases are a dance of texture and form, probing today’s fleeting obsessions and tomorrow’s forgotten images. Undaunted by the fast-paced buffet of modern imagery, Yaeger vividly portrays our complex relationship with images, examining how paintings contribute to this dynamic.

I’m exploring or exploiting proclivities or attractions within myself, and, being a self entirely within a culture or society, the mirror is thus held up

Joseph Yaeger

Yaeger explores our obsessive adoration of images, weaving in themes of desire and allure. He selects subjects from an array of images, guided by an indescribable instinct from his subconscious. His creative process is an introspective journey, reflecting Yaeger’s expression of interests, feelings, and the external world, materialized on canvas. While his work doesn’t overtly focus on societal or cultural statements, it subtly acknowledges these themes as an inherent extension of his perception of society. Yaeger captures these sentiments in realistic close-up, almost abstract scenes, radiating a cinematic aesthetic.

To prepare his masterpieces, Yaeger sprays his canvas from a distance with water on drying gesso, then starts painting with watercolours to form his image. This technique creates a textured surface, is a hallmark of Yaeger’s experimental approach, and often influences his choice of subject matter.

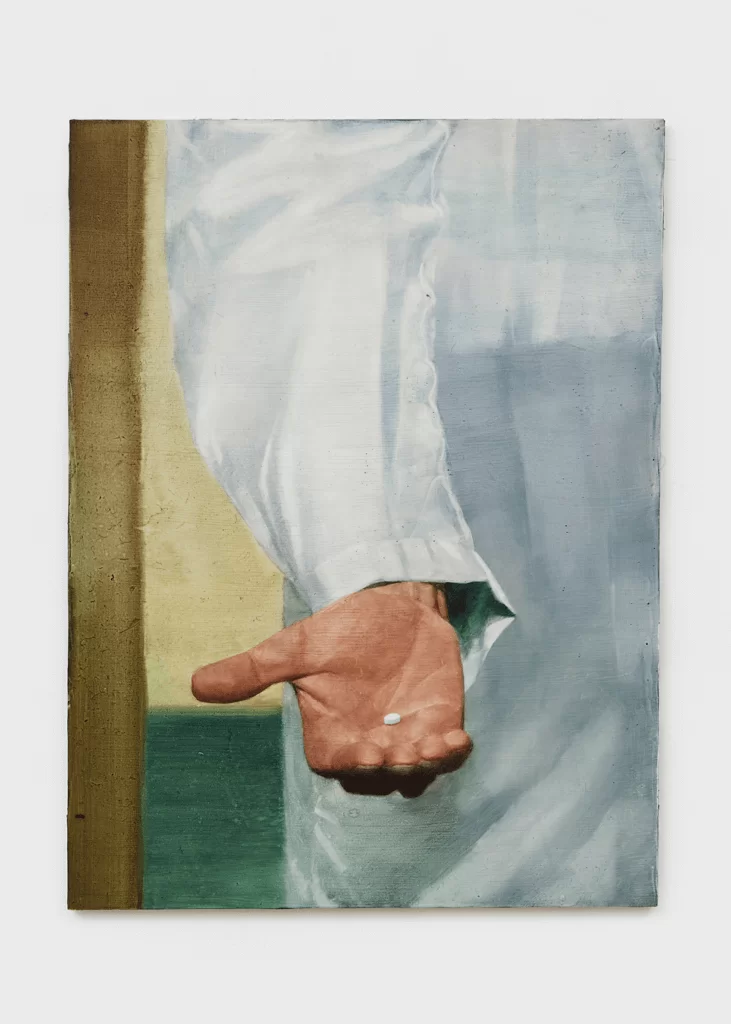

We witness this in his works, such as “Freedom from Want,” for example. This chilling portrayal of a doctor in a white coat, poised with an open hand offering a pill like a modern-day Prometheus, encourages more literal interpretations from its abstract representation and sweetens the painting’s enigmatic quality. The piece isn’t just a scene; it’s a mystery of the seen and unseen. Yaeger meticulously renders every crease and contour of the hand, casting subtle shadows and employing warm skin tones to suggest the tangible sensation of blood flowing beneath the skin, achieving a captivating realism that’s hard to look away from.

Freedom from want, 2022

Watercolour on gessoed linen

140 x 105 x 4 cm

55 1/8 x 41 3/8 x 1 5/8 in

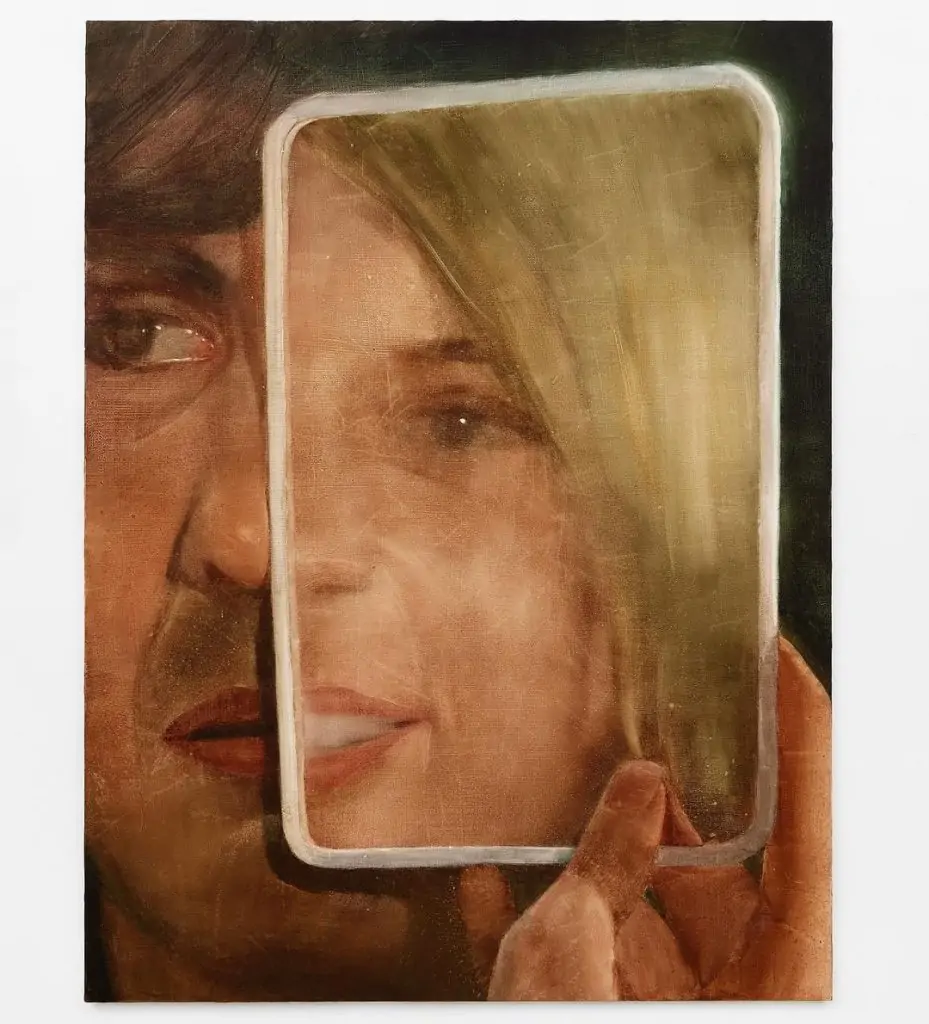

Then there’s “Lost in the Original,” a zoomed-in view of a pair of eyes that convey a sense of being lost, with a gaze suggesting horror, shock, or feelings of instability and unpredictability. Both of these contemplative scenes leave you in awe like most of his work.

Yaeger’s paintings exudes Kubrickesque chills of visual storytelling, wrapped in an aura that’s as unforgettable as it is intriguing. In filmmaking, there’s a style known as Cinéma vérité, French for ‘truthful cinema’, meaning unveiling the truth and highlighting subjects hidden behind crude reality. Yaeger seamlessly incorporates this raw honesty into his works, which are marked by their psychological depth and ambiguity. I feel Yaeger’s work perfectly embodies truthful painting in this context, steeped in detail that invites deeper interpretation. During his participation in group exhibition Accordion Fields at London’s Lisson Gallery, we had the opportunity to catch up with Yaeger, an artist to watch, and learn more about his practice, inspiration, and artistic journey.

Hi Joseph, could you share with us your personal journey and how you ventured into the world of arts? What drove you to embrace an artistic career?

Joseph Yaeger: It’s funny I can’t recall a time before I was attracted to either imagery or the image without wanting or needing to translate it into two dimensions. I can remember being a very young boy and finding on basketball cards images of Mark Price, point guard for the Cleveland Cavaliers, to have been imbued with some kind of essence, an arrangement––not an attraction to Price, per se, (this was many years before puberty and sexual attraction) but his image––such that I needed to depict it.

I would do my best to transcribe the images, which were usually of him mid-shot, starting with the airborne feet and ending with the basketball about to leave his fingers. His image was beautiful, and my attraction to it, I grant, was close to that of a fetish, minus perhaps the connotations. I suppose everything since then has been a kind of extension or extrapolation of this urge or compulsion––an inexplicable obsession to the without, somehow describing an aspect within.

Your practice delves into modern culture’s memory and value systems, focusing particularly on how society prioritizes images and visuals and the role of painting in this context. Could we explore your practice, inspiration, and approach to these themes in more depth?

Joseph Yaeger: To some degree I believe this is accurate, but it’s difficult in that this not how I go about painting itself––I do not think of ‘modern culture’s memory and value systems’ nor ‘image prioritisation’ as I begin a painting. I would say that I’m exploring or exploiting proclivities or attractions within myself, and, being a self entirely within a culture or society, the mirror is thus held up. Often incidentally. Because the aim is never outward. I’m never ‘holding up a mirror’ in any kind of didactic manner. I would almost say the work is actively against such notions, though I appreciate certain artists who swim in those waters.

I’m externalising an interior, to an interior, and an exterior happens to be in attendance. Nothing in this sense is prescriptive, or critical, or judgmental, or analytical––at least not in individual paintings; once the paintings are exhibited, and their interdependent arrangements can be determined and fixed, then perhaps some comment or nod toward the (or a) state of things might emerge, but it is only in retrospect that I fully understand what was and is being articulated in the images themselves.

This is why writing precedes any and all painting for solo exhibitions. Someone recently said I was attempting to create a perfect cinema, one without chance or collaboration, writing a long text or ‘script’ beforehand and then filling the linguistic aspect with stilled and highly controlled images of my own choosing, and I suppose that’s true, however in selecting images to paint it’s quite important that they correlate or harken to the history of painting in some way. In this sense, as well as the fact that I purposefully avoid recognisable or ‘iconic’ cinematic scenes or characters, the translation into paint is a kind of de-cinematising of the image.

Building on this, how has your experience in film school and your ongoing fascination with cinema influenced your choices in subject matter and composition in your paintings? Do cinematic techniques, such as framing or lighting, play a role in how you approach a canvas?

Joseph Yaeger: I think it has to do with the formation of the self. So much of my conception of who I am in an artistic framework, where my values lie, how my aesthetic sense may be engaged, happened somewhat by accident many many years ago, as a teenager, seated before films I was ostensibly posing (even to myself) to enjoy or like, for reasons that even to this day are obscure to me, alone in my room, rented from Netflix back when it was a DVD-delivery service with those little padded paper sleeves, sometimes almost forcing myself to sit through to the end, with the occasional breakthrough of transcendence (Taste of Cherry, 2001, Russian Ark, Songs from the Second Floor, Mirror, 8 1/2) so thoroughly prying me open that I can remember sitting in front of the television almost drooling, breathing very shallowly and feeling like light was throbbing out of my chest, knowing I must make movies. That in an almost religious sense I heard a calling.

Of course I was wrong––it is unlikely now that I’ll ever make a movie, however all of my work in some way grows out of that sensation I once felt, intensely, fixed before a screen as a 15-19 year-old. So the answer is yes: cinematic and photographic techniques play a critical role in how I approach a canvas or composition, likewise how I see reality itself. Of equal importance was theoretical writing on the two mediums. Barthes’s Camera Lucida and Deleuze’s Cinema 1 & Cinema 2, to name a few, gave name and language to facets before which I’d only fumblingly and intuitively felt, and genuinely changed the way I watch movies. This of course meant my paintings, downstream––as it were––to cinema, changed as well.

Lost in the Original, 2023

Watercolour on gessoed linen

46 x 87 x 2 cm

18 1/8 x 34 1/4 x 0 3/4 in

Your work appears to evoke a sense of fleeting memory and impermanence. How do you achieve this effect through your technique and choice of subjects? Is there a personal significance to these themes in your work?

Joseph Yaeger: It seems to me fleeting memory and impermanence are alternative (or glib) definitions for living, so I suppose any evocations of these effects are achieved through close observation of what it feels like for me to be alive. I realise this seems like wordplay or like I’m dodging the question, but I mean it sincerely: for instance, basically everyone to a degree knows what it feels like to thrust dental floss too far into one’s gums––that numbly pinging, wet pain––but it is only through working and reworking over time that one might learn how to translate that physical sensation into a visual one.

(The visual must use everything it can––it being a weak sense on its own––to evoke the other senses, which is where the cinematic techniques of intensifying lighting, framing, etc come especially into play.) This isn’t a painting I’ve made, because no paintings are conceived of before they’re encountered in preexisting media, but the principle is the same: decode and extract from the moving image some obscure aspect that will, in being fixed, be elevated, and potentially act as an open metaphor for other uses. If an image tells us what it’s about directly, then it is ‘closed’, and is essentially functioning––in a Wittgensteinian sense––like language, and I feel sort of allergic to these types of images.

Perhaps unexpectedly, I find the simpler an image, information-wise––achieved usually through some form of cropping––the more open it can become. The more open, the more combinatory. Simplicity, I should say, plus something happening. Something happening can be a certain tone of green in the background, a gesture, a point of contrast. It doesn’t have to be an action verb, but it does have to distinguish itself emotionally. Sort of like how ‘New Grass’ by Talk Talk––a chorus-less, nearly 10-minute wander––can somehow be ‘about’ the piano chords that come in at 3:20 and 6:45.

Additionally, your paintings seem to emanate complex emotions and subconscious recollections. How do you balance the emotional resonance of a piece with its visual representation? Is it a matter of prioritizing one over the other, or do you find it to be a harmonious process?

Joseph Yaeger: Absolutely no aspect of this is conscious. I don’t know. What I will say is whatever is going on in the painting, I hope, is exactly how I feel or felt within while making it. And likewise I hope that that feeling is passed on to whomever sees it out in the world. In this sense I relate it to method acting, in which I call up parts of the self or sense-memory to make real/true/alive the two-dimensional mud-smear I’m creating.

Could you discuss how the unique textures in your paintings, created by layering watercolour on gessoed canvas and using techniques like water spraying and canvas manipulation, enhance the narrative and emotional impact of your works?

Joseph Yaeger: Like most of the answers, these narratives are more personal than anything. This doesn’t, however, mean they are a secret. I was very moved by Anderson’s decision to have Reynolds Woodcock hide messages in the linings of his garments in Phantom Thread. Most of my paintings contain their own ‘never cursed’.

You’re right in saying layers exist, but they’re a prelude to the watercolour, which is one single layer by necessity. It’s not so different than those diagrams of the layers of the earth we all encountered in textbooks as children: the core and mantle are deep and thick and volatile, whereas the crust by contrast is incredibly thin and simple, but enacts in some way all the complexity lying beneath.

The watercolour, in other words, is just surface, a projection, gossamer-thin, laid over many layers of gesso, the physical build-up of which denotes time. The layering of gesso contains all sorts of things within it, stirred into slurry, signifying the date and general mood of its applications––tea leaves, tobacco, hair, dried plants, preceding paintings, dust, studio detritus, staples, fluids, etc––such that a narrative almost naturally is drawn. This can take weeks or months or sometimes years. I recently finished a canvas that I began gessoing in 2019. The paintings themselves are graveyards and construction and renewal at once.

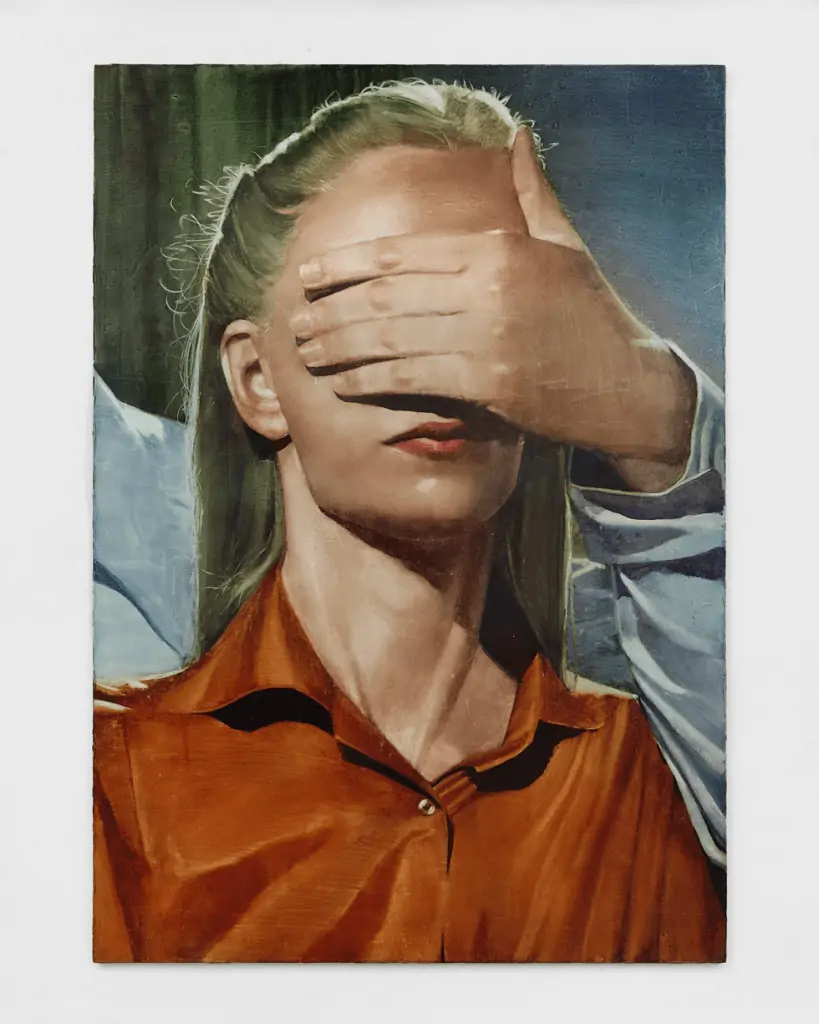

Would The Fire Mysterious, 2023

Watercolour on gessoed linen

You’ve mentioned that there’s much more to explore with watercolour as a medium. How do you see your work challenging traditional perceptions of watercolour painting, and what future explorations do you have in mind for this medium?

Joseph Yaeger: The shallowest answer probably reveals my own perception of watercolour as a medium, which is one practiced by retirees, Sunday painters, the plein-air-landscape-on-cold-press-paper crowd. This is probably outdated, and definitely nothing to smirk at, but it also seemed fairly primed for subversion.

At this point, I believe the formal aspects of my practice have a lot in common with writing fiction in that they sort of implicitly ‘lie’ about what they are. The medium itself is pushed beyond what it wants to or maybe was even designed to do––watercolour does not adhere in any way to the gesso, so pragmatically speaking, the act of painting is quite challenging––in order to confound and dislodge the sub- or unconscious expectations. The fact that they look like oil paintings is not accidental; my hope is that when one studies the work up close, they feel dislodged by their ‘not-oil-ness’. I know when I see certain works by Celmins or Ruscha, say, works in which the hand of the artist is either concealed or camouflaged, that initial question of ‘how?’ complicates my entire subsequent relationship with the painting or drawing, always in a positive sense––a bit like one of those 2001 apes approaching the monolith.

Secondarily, I feel or felt like it’s still pretty open, practitioner-wise: we have only a handful of capital-M masters, really, as I see it. Sargent, Wyeth, Turner, Blake, maybe Nolde, maybe Hockney(?). This is just off the top of my head, but the point is that with the exception of Wyeth and Blake, few artists have ever used watercolour as their primary medium in a context aimed toward art history and not like … expensive tutorials exploiting a single ‘trick’ others might pay for access to learn, Bob Ross style (plus merchandise!).

Regarding future explorations, I think that very notion precludes knowing what’s beyond the horizon––I will say that density of application is interesting me right now in the studio: how saturated––ie the chroma of light––can a painting become before either the medium’s or image’s stability begins to falter. Assuming there is one, where is the breaking point?

To learn more about Joseph Yaeger head over to his website of Instagram link below

https://www.instagram.com/jsyaeger/

©2024 Joseph Yaeger