From the 29th of July to the 25th of September 2022, interdisciplinary artist Osman Yousefzada‘s site-specific installation works will transform London’s Victoria and Albert Museum into a bridge between cultures in the artist’s first major solo exhibition in London.

“What is Seen and What is Not“ is Osman Yousefzada’s completed body of work commissioned by the British Council in partnership with the V&A and Pakistan High Commission. It is part of the British Council’s festival season programme, ‘Pakistan/UK: New Perspective.’ Yousefzada has been asked to respond to Pakistan’s 75th anniversary, and the resulting work is a multifaceted investigation into history, migration, displacement, and critical global issues.

I am a second-generation son of immigrants born in the UK, and the layers of the space I occupy – my identity and class are paramount to the work I make

Osman Yousefzada

Osman Yousefzada’s new work features a series of interventions. Drawing on a personal connection to the UK and Pakistan, Yousefzada’s work contemplates identity in the context of national and personal history. Viewers will find intersections between ancient imagery and contemporary contexts as Yousefzada carefully weaves together Pakistani and South East Asian culture symbols throughout large-scale textile pieces.

The artist is particularly concerned with themes of displacement and migration experiences. Yousefzada weaves these subjects together with material representations of movement and travel in his series of domestic object sculptural works. In an outdoor garden installation, the artist creates space for contemplation and investigation into issues of water dependency in the age of climate change.

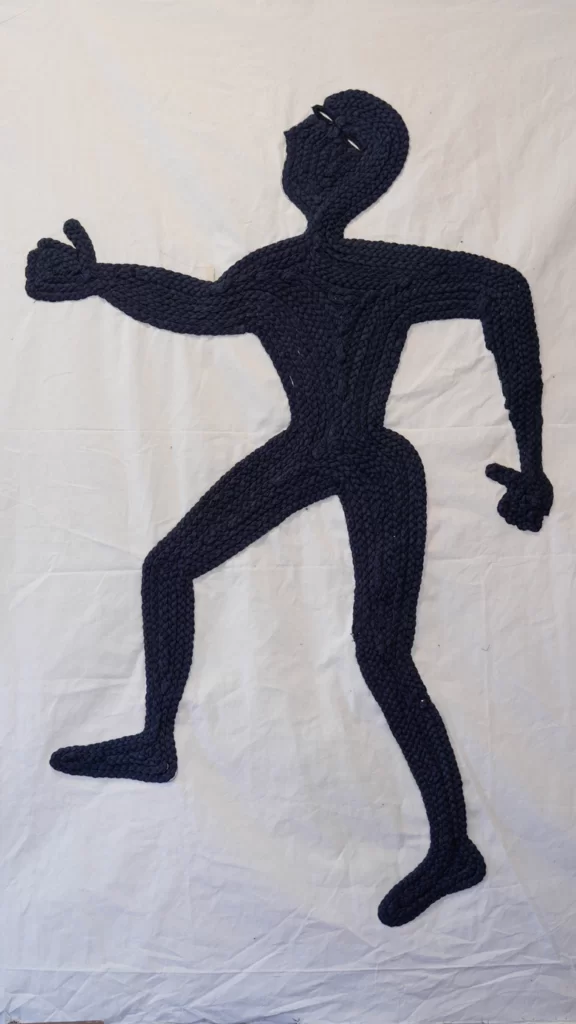

This new commission features an exciting range of techniques and materials. Yousefzada’s new stitch technique stands out against the use of traditional craftsmanship often paired alongside paintings. Throughout the exhibition, Yousefzada manipulates space to reference transcendent places like shrines and ritualistic traditions while also incorporating dialogue with colonialism’s roots and impact, looming climate issues, and universal themes of movement.

Yousefzada’s V&A intervention is sprawling. The artist’s approach to reflecting on the 75th anniversary of Pakistan carefully considers the influences that shaped the nation’s history and presents ample opportunity to imagine its future. “What is Seen and What is Not” gives viewers a comprehensive picture of a national culture not only because Yousefzada has carefully adjusted the lens but because the artist has focused on using his unique and personal perspective. This bridge between cultures was built thoughtfully and with care.

What is Seen and What is Not is on view at the V&A from 29th July to 29th September 2022.

Your works within What is Seen and What is Not reflect your personal perspective on migratory experience and identity. What was your goal in creating work for this project, and how did you first begin to approach these topics?

A: Most of my work has an auto-ethnographic disposition. For me, these experiences are the way I view the world and my positioning and narratives. I am a second-generation son of immigrants born in the UK, and the layers of the space I occupy – my identity and class are paramount to the work I make. Space is political. My work is personal, but it’s the personal that becomes political. This three-part series of interventions is about spaces, its histories of rituals and our relationships across global, colonial, and environmental spaces.

The works lean on domestic interpretations of safe spaces, tapestries that become Talismanic, a stronger version of you. Like a superhero, the wrapped objects function as rituals of ownership and consumption in the migrant process. The installation in The John Madejski Garden is about communal seating that allows a different perspective of history to be viewed by sitting on the charpai’s and mora stools, looking out onto the layers of histories at the V&A.

Q: The work in this exhibition references shrines and spiritual spaces. What prompted your interest in this theme, and what is the significance of presenting them here in the U.K?

A: These ‘safe’ spaces, which I see as ritualised spaces, interest me. We create similar re-constructs in our lives – rituals that allow us to face the world. The migrant has an even more distinct space, a sense of magical realism that carries stories over borders that are re-imagined in minds and spaces through food, language, dreams of hope and aspirations. A better life. A life that begins again. I see such domestic spaces as shrines and ritualised spaces that allow people to sustain their existence from what was once familiar. Especially the types of migrants who don’t possess the codes to fully integrate themselves into their adopted homeland.

So, these spaces are re-constructs and re-imaginations of shrines where you go with the hope of having your dreams fulfilled. Where you can transcend into alternate spaces, where you feel as marginalised and the other – it’s this voice that somehow attains power through these spaces, that you are both the portal and the key to change.

Q: How did you approach the material and construction of the new works you’ve created? What is significant about the medium and material you’re representing here?

A: There is a lot of textile narrative in the works, from the off-loom tapestries, which are a new medium and a re-interpretation of my paint/print-making practice. For the tapestries, I worked with artisans in Pakistan (these artisans mostly make glittery bridal dresses). I found various materials cast off from garment factory floors, which we spun rope from. With these unconventional types of materials, and offcuts of used fabrics, each with their unknown histories and memories, I developed new stitches and techniques for storytelling on the tapestries in the first part of these interventions.

The wrapped objects, which are a totem in the sculpture gallery, are executed in ceramic and glass versions of fabric-wrapped objects that I’ve made previously for my solo show at the Ikon Gallery. It’s these folds that are captured in the drapes of the barrier – so the fabric is as much a storyteller, a muster of other works as well as a barrier. Then again, the charpais become horizontal tapestries this time, rope fabric waste is lampooned and webbed onto salvaged colonial architecture.

Q: How does your new work reflect on Pakistan’s independence while also exploring the country’s relationship to colonialism and its intersections with South Asian culture and identity?

A: My work is from a diasporic lens, someone who feels at home in the UK but also connected to Pakistan. When I go there, I feel as if I am one of many, but as you peel away the onion layers, it has its own narrative of class, elitism and ethnicity. As a diaspora, we seek safety in numbers abroad; we look toward other faces of South Asian descent to mirror our experience.

When I’m in Pakistan, that isn’t so; it’s a country that was violently erupted out of a larger mass. Its birth was violent – millions died for it to be born, and a line was drawn by its colonial masters in a matter of months that fated your existence. If you were on the wrong side of the line or not, then you would need to move, with no guarantee of safe passage. It’s these tremors and repercussions that are part of the wider narrative that still needs healing. Some want to see, and others don’t, but the healing from this rupture needs to happen so the stories can move on.

Both countries want to move past it and see themselves as bright shiny new economies that are the promise of economic development, yet the trauma that they carry is the weight that holds them back.

Q: Issues of climate change and the environment are incorporated into this new body of work very strongly. Where does your concern for environmental challenges impacting Pakistan appear in the pieces you’ve created?

A: I think people aren’t very aware of why climate change is such a big issue for Pakistan; it’s the fifth most vulnerable country that will suffer from global warming. You are already seeing it from the freak floods and changing temperatures that break records yearly.

These higher temperatures are destroying glacial Himalayan reservoir capabilities as it can’t hold retain water in higher temperatures, so you are looking at peak flow by 2050, and then water scarcity for one of the most populous countries in the world. The boat in the installation is key. It takes the position of a colonial ship, dark and ominous, looking to expand and extract from distant shores.

These global expansive and capitalist relationships are detrimental to countries like Pakistan, which only contributes to less than 1% of global gas emissions; however, it is the fifth most vulnerable country to global warming.

The boat was made by fisherfolk who inhabit the mangroves of Karachi and whose lands are being swollen up by commercial expansion domestically. The loss of the coastal mangroves has devasting effects on its surrounding ecology. Also, in a post-colonial world, where the global south is still subjected to being a second-class citizen, some of us roam the world like slaves and others like masters – the boat highlights the climate emergency.

Q: Your new work links Pakistan’s past and present identity and serves as a bridge between cultures. Was it helpful to draw on your own unique personal perspective in creating these works? Do you see yourself situated between past and present, or between cultures at all?

A: I see myself situated in-between spaces, a place to observe others as the observer and be situated in difference. The past always reimagines the future, and the storytelling is key to my offering of how Pakistani and British Pakistani’s and any other migrants can see themselves.

The Story of Pakistan is its birth in 1947 – but its people and the Indus basis have lineage to one of the oldest civilisations on this earth – Meher Ghar, which is nearly 11,000 years old. The work I wanted to show, especially in the tapestries, is the ancient past of Pakistan’s identity, and it’s that infinite culture that gives its deep foundation and a bridge between the past and present.

Q: This exhibition deals with heavy topics but also seems to consistently create space to contemplate and reflect. How did you strike this balance in your work, and why did you feel it was important to do so?

A: I think as the works are site-specific, they needed to have space to be able to contemplate and reflect on the socio-economic issues addressed by the interventions. It’s the space between that is sometimes just as important as the work itself. The charpais and the mora stools allow for a new position for viewing the V&A in its colonial inception, its conversation of textiles, cotton and Chinz as the impetus behind colonial expansion.

It’s those same neo-colonial structures that produce garments for the high street, and it’s their waste that I have appendage to salvaged doors highlighting the intrinsic relationship of textiles and how the neo-liberal relationships of the global north and global south divide and the industries that pollute such as the Petro-chemical industry, whose waste is once again dumped into the developing countries.

Q: Did you find that thinking about the topics of migration, climate change, colonialism, and displacement specifically within the history of Pakistan has influenced your perspective on how these issues play out throughout the world? Do you think this exhibition allows viewers to apply what they see and feel in your installation to the broader outside world?

A: I think the issues facing Pakistan are also global issues of migration and diasporic connections and the brain drain of those wanting a better life and their connections back to the countries of their birth and their offspring and its rather different relationship. Of colonial wreckage and structures that are still inherent and have a bias and perpetuates some countries which have never been able to catch up. Of global warming and dumping grounds, these are all universal stories of identity, class, environment and space.

©2022 Osman Yousefzada