Umar Rashid: En Garde / On God

6 November–18 December 2021

Blum & Poe

2727 S. La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90034

USA

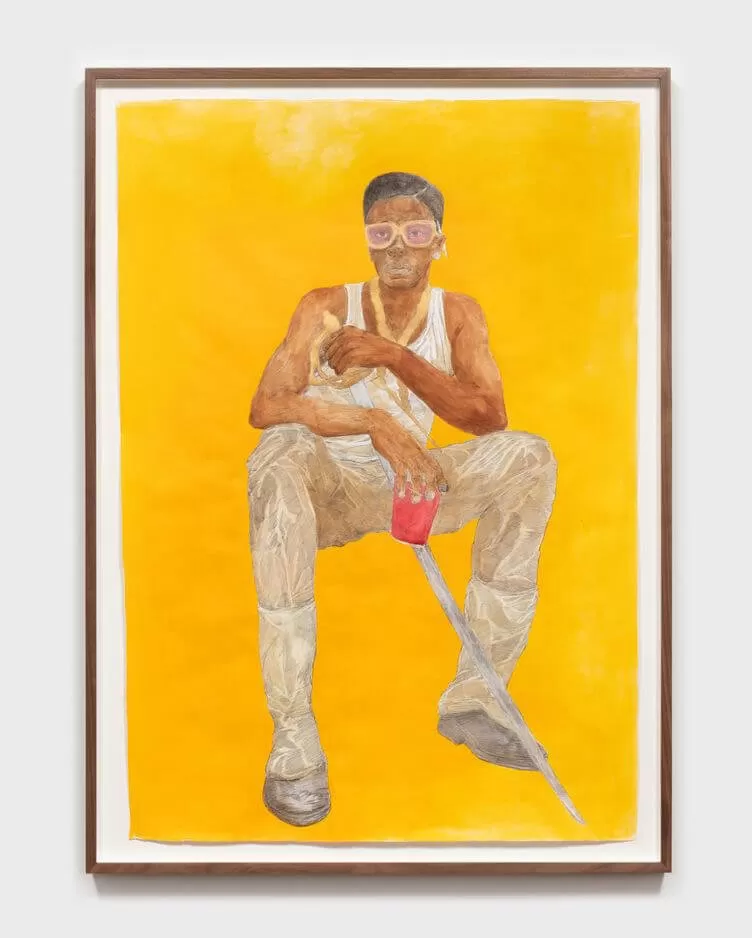

Blum & Poe is pleased to present En Garde / On God, Umar Rashid’s first solo exhibition with the gallery. In new paintings, drawings, and sculptural work, Rashid presents a new chapter in his fifteen-year-long project of documenting the fictitious history of the Frenglish Empire (1648–1880). Informed by the storylines that are encoded into the canonical narratives of empires and their colonies, and even more so by those that are marginalised and omitted from the historical record, Rashid conjures a world replete with complex iconographic languages that use classifying systems, maps, and cosmological diagrams.

Channeling the visual lexicons of hip hop, ancient and modern pop culture, gang and prison life, and revolutionary movements throughout time, in these works Rashid seeks to underline the roles of race, gender, class, and power in the problematic history of recounting history.

In his one-paragraph story On Exactitude in Science, Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges evokes an unnamed, unlocated empire so taken with precision in the art of mapmaking that its cartographers eventually produced ‘a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.’ Later generations did not share this taste for exactitude and, failing to see the point of such a map, abandoned it: ‘In the Deserts of the West, still today,’ the story ends, ‘there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.’ Goodbye geography: a discipline gone so awry it managed, if only for an instant, to let the map take over the territory.

Consider this ruined map: an onion-skin paper copy of a whole empire, crumbled, ripped and torn to garlands, reduced to strings of origami mausoleums to the real world. All so uncanny and grotesque until, perhaps, following the trail of Borges’s facetious clues, we come to ponder precisely what in an empire is tangible beyond words.

Sure, the land that empires claim can be captured, dug into, turned over, occupied, and marched upon. But empires are also made of stuff less concrete than land—myths, lies, dreams propped up or trampled, stories sweetly whispered into some ears and loudly hammered into others. Empires are built on mountains of corpses, but the real issue is that corpses will speak if you let them. Empires may glory in, or turn away in shame from, blood spilled; either way they get, and write, over it, tying together true accounts with golden strings of make believe. This is also the way imperial maps are made. They are designed to cover endless expanses in a slick veneer of words, the better to hide the endlessly overlapping layers of lives and waves of deeds, each round covering the last, building monuments here and eroding them there, shaping the landscape beneath.

Still, every corpse has a story, though imperial narratives may require such tales be discarded. They poke through, punch holes, always a challenge to the official story, always threatening to ruin the purported totalising exactitude of imperial cartography. In 1834, the poet Lydia Sigourney Huntley prefaced her Indian Names with the following question: ‘How can the red men be forgotten, while so many of our states and territories, bays, lakes, and rivers, are indelibly stamped by names of their giving?’ Huntley was playing coy: Native Americans did not give these names so much as Europeans exacted and repurposed them to hide their violent deeds. Behold this feat of cold alchemy: words summoning a nation into being, cooking up countries out of carnage, and vanishing people into thin air. Imperial maps do not lay literally over any land; they do it figuratively, and their ‘tattered ruins’ are everywhere, in names marking the land in permanent ink.

What if you set out to reverse the process?

Umar Rashid once went by Frohawk Two Feathers—a nom de plume he gave himself and has now given up. This shedding mirrors the enormous task on which he set out years ago: to uncover and represent what lies underneath the names on the tattered map we so often mistake for history. Rashid’s work reverses that of Borges’ cartographers: wherever he goes, he raises lost, unborn provinces and empires out of the relics of their dreams. Rashid’s work does not dabble in the pretend exactitude of Borges’s uncanny cartography; it excavates the states buried in the margins of unread history books. It summons the truth that lurks between their lines.

Before it was the thirty-first state in the union, California was an independent republic for less than a month; it had been two provinces of the First Mexican Empire, once independence stripped it of its former name of New Spain.

In Alta and Baja California, provinces the size of a continent, European power resided in a network of Jesuit missions that doubled as military forts, sites of temporal and secular oppression all in one: so many names of saints strung on maps like the beads of a rosary. Before the monks raised their crosses, conquistadores had drawn the path and, again, always given names. Faced for the first time with the gigantic region, they glued the territory to a dream map: Montalvo’s sixteenth-century bestseller, The Adventures of Esplandían, depicts the island of California, populated only by strong Black women, tamers of bloodthirsty griffons, and ruled by Queen Calafia.

The heathen Amazons hear of Europe’s religious wars and see a chance for the world to learn of their courage, but the California girls, their griffons, and their queen are subsumed into European storytelling. Calafia marries a knight and comes back to California. Game over, says the narrator: ‘We decline to say more about what became of them because, if we wished to do so, it would be a never-ending story.’ There must be a beginning and an end; borders in place and time—however arbitrary—that reinforce fables of uniqueness and hide how much of history is made of the same mistakes.

The Frenglish Empire, whose history Rashid’s works chronicle in every corner of the known world, may have never actually existed; yet you will recognise the missions, the warring factions, snippets of colonies and empires reshaped as global tides of war and trade meet numberless individual trajectories. You will hear familiar accents in its tales of heroism and petty opportunism; in its portraits of heroes and villains— bloodthirsty, gold-hungry colonisers and the religious officials who absolve them; former imperial soldiers finding in alliances with indigenous rebels the true meaning of freedom; peasant women forced into lives of vengeance and violence; hapless rulers killed in their sleep and the nameless masses who cheer the deed. The artifacts, the battle-worn flags, the ancient maps: the remains of days that, though they never were, will make you wonder how much you actually know about those that have been. And why.

En garde: walk in armed and ready. Though playful and humorous, Rashid’s work should not be taken lightly. It comes bearing a challenge: when you dare to look through the tears in the map, whose history do you see?

Which of these nations would claim you?

©2021 Umar Rashid, Blum & Poe, Josh Schaedel