Serena Salvadori is an Italian photographer from Trieste, who has travelled and developed her career between Spain, Brazil and Berlin. This interview will explore the way the different places she has lived in have influenced her career path and creative process. Her photographic style is a mixture of different influences she has gained around the world, such as documentary techniques from Brazil and aesthetic portraiture from Spain.

I challenge the person to answer these questions, also using body language, which is emphasized through the aspect of nudity.

Serena Salvadori

Serena’s photography explores the subconscious by depicting a world that is in between dream and reality, a dormiveglia. A recurring element that portrays the state of the psyche is a veil or cloth over the figures, for example in the photographic sequences of Carmen Es Mi Chica, You Don’t Need to Touch to Feel and Come Dice Mia Sorella. Serena’s limbo between reality and dream has also been utilized as a way to distance oneself from traumatic reality and her use art as a form of therapy in I Want to Be a Mum.

Serena’s work is centred around nudity as a way to explore the individual and the collective. The project Antemortem represents the body as an anthropological study to inquire about the bodily responses around the theme of death. Meanwhile, nudity in Ce n’est pas du porno c’est de l’amour, Serena aims at normalizing queer sexuality and love as to contrast the lack of visibility she was accustomed to growing up in Italy.

Q: How did you know you wanted to be a photographer?

Serena Salvadori: I didn’t always know I wanted to be a photographer; I discovered it. I attended the Higher Institute of ISIA of Urbino (Italy), which is similar to IED but public. I studied graphic design for advertisement and editorials. When I studied photography with Professor Lucio, it was love at first sight. The Institute had beautiful printing labs for coloured and black and white photography. Photography was the form of art that allowed me to express myself at best, even though initially its mechanisms and techniques were complicated to understand. I have never felt that way.

Q: How have the places you have lived in the world impacted your artistic practices?

Serena Salvadori: In Italy, I discovered photography. In 2006 I moved to Madrid to take a master in Photography at EFTI Madrid. I then moved to Barcelona and started my career in Spain, where I mainly focus on commercial jobs, for example, in fashion, editorials and collections for designers. My friend Thiago Coelho, almost a brother, invited me to Brazil in Porto Alegre.

There I get closer to reportage photography. I had an artist residence in Galeria Mascate and worked in Estudio Barraco. Then I moved back to Europe, to Berlin, for five years. There I had an artist residency in a gallery for two years, and I came in contact with the underground and queer scene. I met lots of different artists, as the gallery is also a co-working space.

According to the different places I live in, my photography is directly influenced. In Berlin, I came in contact with documentary and autobiographical documentary photography. However, in the last years, I developed my style: a blend of techniques of documentary and portraiture with an aesthetics background I developed working in the fashion sector.

In Berlin, I developed Antemortem, a project about the human being, this is where I step out of my comfort zone, and I create an entirely different project: I photograph naked bodies of people I have never met. While they are exposed, I ask them three questions: What do you live for? How present is death in your life? What image would you like to see before you die?

I challenge the person to answer these questions, also using body language, which is emphasized through the aspect of nudity. This project has nothing to do with sexuality. I have been working for seven years on this project with four main sessions: two in Berlin, one in Brazil and one in Spain. These photographs are social and anthropological as the questions stay the same, but according to the culture I am set, the reactions of the subjects photographed are different.

Q: What was the turning-point in your career?

Serena Salvadori: In 2012 I had my first solo exhibition of Carmen Es mi Chica in La Plataforma BCN. The feeling is incredible because the exhibition space is all yours, you have more liberty to choose the frames of the works and how the exhibition will go. You get to see the way people react physically to your photographs. During my artist residence in Galeria Mascate, in Brazil, my artistic career began.

I am a photographer, and my projects are for myself but also for others: when people see my photographs, they can identify themselves through them.

Q: Is photography a vehicle for reality?

Serena Salvadori: Yes and no. In my case, I play with reality and create photographs between reality and dreams, through which I modify the existing facts. When the audience looks at my photographs, I want them to question whether it is reality or a dream.

I have the liberty and creativity to reproduce images that remind me of my dreams and my subconscious through the use of colour, as I give certain colour tones to the photos, with a subtle sense of surrealism. For example like in Come Dice Mia Sorella (Like My Sister Says).

Q: Can art be a form of therapy?

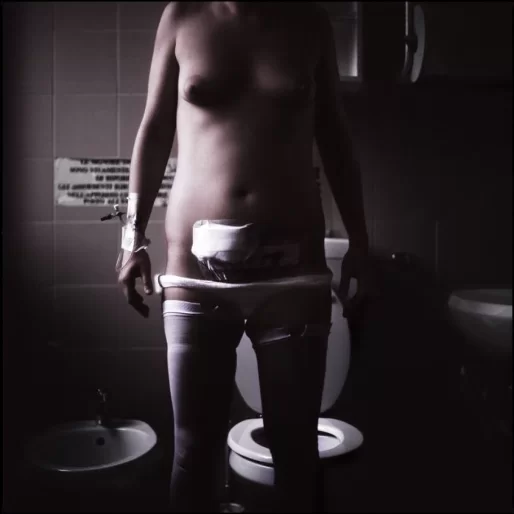

Serena Salvadori: Yes, absolutely. I was influenced by phototherapy in the work of Jo Spence. While she had breast cancer, she invented phototherapy: during a situation of trauma, having your portrait taken or recreating absurd pictures can change the energy in such a dramatic moment and transforms it into a game. The influence of Jo Spence can be seen in the series I Want To Be A Mum at 27 years old. I was diagnosed with a benign myoma in the uterus. I fought for two years as I risked to have my uterus removed.

I decided to report the process of the surgery: The before and after. It is a very uncomfortable situation. For example, when the nurses were cleaning my genitals, I decided to take a picture. Taking these photographs allows me to distance myself from the current dramatic reality. This is the phase of production. Meanwhile, when you develop and print the images, you realize that your agony is imprinted on paper. It’s a way of changing energies. Later on, I Want To Be A Mum won the prize at Photo Festival in Lodz, Poland.

Q: What relationship do you build with the figure of your portraits?

Serena Salvadori: In Antemortem, to make the person feel more comfortable, I photographed them naked myself. This way they don’t feel like I’m the photographer, but i’m a human being like them as I am naked like them. Initially, I wasn’t naked while taking pictures. This method allowed me to get closer to the subjects through the gaze and to emphasize. Usually, I photograph what is around me and the love that I feel for people such as my great loves, which were like muses to me but also my nieces in Come Dice Mia Sorella (Like My Sister Says).

Q: How is movement perceived in your work?

Serena Salvadori: I am very classic in the techniques of photography as I use a tripod and Hasselblad. Therefore the image is very static. I allow the subject to dance within my photos. It also depends on the project itself. For example, in Antemortem, I did not know the people I was photographing. Therefore movement depended all on the relationship that was created between me and the subject. According to its responses to the questions, it would move differently.

Q: In what ways is sexuality portrayed through your work?

Serena Salvadori: There is always a part of me in the picture I take; I photograph people and lovers. People I share moments with. My work is about humanity, gender and identity. I am a white European, born in Italy, and I live in Europe. I have the luck and social situation that many in the world currently do not have. I feel involved in this current situation.

Carmen Es Mi Chica is images of human beings that I didn’t have the chance to see when I was young as I grew up in 90s Trieste, in Italy. There were no images of homosexuality and queerness. I wanted to normalize the vision of love and liberty for other human beings so that that next generation youths could view this existing reality, different from the typical Italian reality of the traditional catholic family. The purpose is educational and political. Gender, sexuality and race are all intersectional. I am a lesbian, I am queer, and in my photography, I want to be coherent with myself.

Q: How can art be a vehicle for redefining women’s body?

Serena Salvadori: There is a need to escape the current schemes highlighted by the fashion industry, such as the anorexic model or the typical idealized Italian woman such as Monica Bellucci. This is also about man’s bodies and their depiction as being perfect.

The truth is that perfection is boring; perfection doesn’t exist. Imperfection is the beauty and characteristic of a person. I want to recreate images that people can identify with. This is a reason why I don’t portray models, but rather people met on the street or in a club, in casual everyday places.

Q: Referring to the series Ce n’est pas du porno c’est de l’amour, what is the difference between porn and art?

Serena Salvadori: In Ce n’est pas du porno c’est de l’amour, you can see genitals in the foreground; therefore it is very explicit. Sex is love. Porn can be art, and anything can be art. The title is ironic itself: It’s not porn, it’s love. In Berlin, I met a queer photographer, and she’s one of the first that took photos of queer porn. I asked her the same question.

And she answered that she didn’t have the chance to see anything like it when growing up, and she wanted to create images that portray the relationship to sex, that normalize porn. You can show on the news a priest that rapes a little girl, but if you show acts of love and sex between couples its considered porn. It’s not just porn, it’s also porn.

Q: How is the sense of touching developed through the images in You Don’t Need to Touch to Feel?

Serena Salvadori: Me and my ex-girlfriend Cloe just broke up, but we were forced to stay together during the quarantine. This project is a case on phototherapy. I had to try not to go completely crazy, living in quarantine with your ex. So we decided to create this project. There are two aspects relevant to the touch in the series. As I am no longer in a relationship with Chloe, I no longer touch her. At the same time, we were living in a world where we can no longer touch each other due to COVID-19.

But even though we can’t touch, it doesn’t mean we can’t feel. The use of plastic in the portraits emphasized a feeling of claustrophobia. Imagine living with a person you love that no longer wants to be with you, it’s a suffocating feeling. I wanted to portray the discomfort of this situation. The contrast plays with the image of naked skin. I was inspired by the work of Robert Mapplethorpe. He is the first photographer to portray queer S&M. Plastic is a recurring element in his works; however, I use it to explore something different from S&M. The naked body underneath is like a piece of meat you buy at the supermarket, surrounded by plastic. I wanted to make the audience feel uncomfortable while looking at the photograph.

Q: Relating to your collection Come dice Mia Sorella (Like My Sister Says), why have you decided to portray small girls?

Serena Salvadori: The project was born out of documentary techniques. The girls are my nieces, who currently live in Connecticut. They are my family. I tried to see them at least once a year. As we didn’t have a lot of time to institute a relationship between us, I wanted to create something that would remain as time went past. Photographing them became a way to play with them, a play of love. They decided to name the series Like My Sister Says, and I liked it because it highlighted their relationship as sisters. Now they grew up, and you can see the difference and growth through these pictures. You can see how they have changed through time, and now they are young women.

Q: In several of your works there is a recurring visual theme: a veil, cloth or plastic over the eyes of the figure? What is its meaning?

Serena Salvadori: I have never noticed it. The plastic in You Don’t Need to Touch to Feel, has a completely different function as to that of the veil or the cloth, as we talked about before. The fabric in Carmen Es Mi Chica was very spontaneous in the moment. Nevertheless, the element of the veil comes back to the ideas of capturing a reality between reality and the dream. Modifying reality through photographs will disturb and challenge the viewers, thus instigating a series of questions and reflections of the truth in the viewer themselves.

Q: On your website you accompany your work with written text, how do the two interact, for example in the series Carmen Es Mi Chica?

Serena Salvadori: I am dyslexic so writing for me is a nightmare. That is also why I was able to express myself through photography finally. I create a project, and I see images. Like a movie, the series must have a title and introduction; therefore, the text accompanying my work is like a synopsis. Sebastiano Mastroeni is my copyright: I share my ideas of the text, and he helps me realizing it. Initially, when one views an artwork, one has a very subjective view on it.

The text does not erase the subjective interpretation but allows me to guide the viewer closer to my understanding of the photos. The text is a bit like a poem, and it works well with the images because like in Carmen Es Mi Chica, the text is fantastic and dreamy. It builds the characterization of the subjects portrayed in an artistic, impulsive and spontaneous way. In the reportage, there are two characters in the story and the narrative between these two characters. Was what I wanted to bring to life also throughout the text.

https://www.instagram.com/serenaslv/

©2020 Serena Salvadori